Today we salute Lt. Joe Brewster. Platoon Leader in Vietnam and Cambodia.

Growing up in Temple, Texas, there were two things Joe Brewster knew about his future. He was going to graduate from Texas A&M University, and he was going to be a soldier.

There were no fairy tales or make believe stories in this military house. His father, celebrated WWII veteran Olin Findley Brewster, opted instead to teach his children about the ravages of war.

One of the most written about Majors in WWII, Olin Brewster played an important role in the Battle of the Bulge at Parkers Crossroads. With six tanks, one company of infantry, and one company of airborne, he was able to hold off an entire Panzer division for six days.

From a very young age, it was instilled in Joe Brewster he had an obligation to serve his country. An obligation he took very seriously.

His freshman year of college, with his brother already a student, Joe realized he did not have the money to attend Texas A&M. He was at Temple Junior College when he learned of a newly designed program.

His freshman year of college, with his brother already a student, Joe realized he did not have the money to attend Texas A&M. He was at Temple Junior College when he learned of a newly designed program.

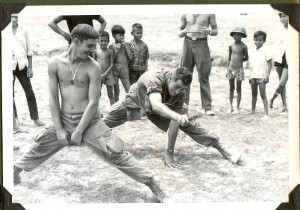

This program would ensure that after two years in the Corps of Cadets (instead of the usual four), he could still graduate an officer. All it required was an extra 9-week boot camp, which Joe completed at Fort Knox in Kentucky the summer before his junior year. At this basic military training course, Brewster was taught to march and handle weapons. He didn’t know at the time, but this course would also put him ahead of most of his classmates.

Joe was accepted into A&M as a junior in the Corps with “freshman privileges.” He wore the black belt instead of the white and was required to wear fish spurs when “spurring” the SMU Mustangs.

A third generation Aggie, none of this phased him. His grandfather, great uncle, uncle, dad, and brother all attended Texas A&M. He knew what was expected.

The summer before his senior year, Joe attended another camp, this one at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In training, he achieved first or second in his battalion, and was then made Platoon Leader of his company back at A&M.

After exhibiting excellence not just in training, but also in the classroom, he was named a distinguished military student (DMS) and would go on to be awarded distinguished military graduate (DMG) in the fightin’ Texas Aggie Class of ’69.

With these honors, Brewster was able to choose his specialty in the U.S. Army. He expected a lot of himself, and knowing he could virtually get anything he wanted, he picked all combat units – infantry, armored, and artillery. He was assigned infantry.

From there, it was on to a 9-week officer basic training at Fort Bening, Georgia. As an insurance policy of sorts, Brewster decided to take additional training.

He enjoyed the routines of Airborne school, but found the real value was in the Ranger course, where he was taught small unit tactics and how to fight in a jungle climate down in Florida. Joe credits his survival to this extra training.

It was then on to Fort Reilly, Kansas, to spend time with an in country unit before being shipped out.

Three short months later, Brewster landed in Vietnam in January of 1970.

There was no welcome committee or on the job training for Lt. Brewster. The man whom he’d come to replace in the 25th infantry regiment, left on the same plane that had brought Joe, claiming his luck had “run out.”

Joe learned very quickly in Vietnam, it didn’t matter how skilled you were, but how lucky you could be. He also remembered his dad telling him to look to his NCOs. They are the backbone of the Army. He remembers a lot of his success came from taking advice from his “crusty” old NCO E7. .

The first night in country was one of those times. After meeting his company commander and being introduced to his platoon, he was thrown into action immediately.

In an attempt to interdict forces and supplies coming from Cambodia, Brewster and his men were tasked to set up ambushes and prevent the enemy from moving through the area freely.

In riverboats provided by the Navy, they formed an umbrella protection for Saigon.

After an hour on the ground, it was mentioned the VC or NVA had found their position, and they should go on full alert. After calling his NCO, he was advised to do a “mad minute,” where the entire group fires at the same time for one straight minute. They received return fire resulting in 4 or 5 casualties. The unit was extracted, but would continue to set up the same type of attacks for the next few weeks.

As the 25th infantry Platoon Leader, Lt. Brewster was very discouraged after his first two weeks. There were supposed to be around 44 men in a platoon, and at any given time, he would have roughly 25 or 30. After 10 or 15 casualties, he questioned his abilities as an officer.

It was then he let his “training” take over.

Joe also relied heavily on intuition. He never made any hasty decisions. In an environment where one wrong step could mean the end, he decided if he and his men were going somewhere, they were going to take their time. They would stop to listen, to smell, and to look for movement. Relying on all of his senses and those of his men, they were able to navigate through the jungles of Vietnam, avoiding treacherous booby-traps set up by the Viet Cong.

He recalls a story of travel through a patch of watermelons. The men were so on-edge, any noise could make them fear the worst. It was a harrowing ordeal moving through that patch; any time a fruit was crunched, it sounded like a pressurized explosive.

During the 11 months he spent in those jungles, he was very upfront with his men. He would share with them the objectives for the day and would always let his men know where they were going. Because they felt like a part of the decision making, this ensured good morale within his ranks.

On two separate occasions, May 8 and May 9, 1970, Lt. Joe Brewster was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for Valor.

The first award stemmed from a situation in Cambodia. Up until then, he and his men had been engaging in small unit combat. The units in Cambodia were much, much larger. His was the first platoon to go in, and they were immediately hit by enemy fire. It was a struggle to fight their way into the jungle and take over a bunker that was heavily defended. Joe was up in the front throughout, directing his men and pulling his wounded out.

The second award involved a misunderstanding with the Navy. The ship Brewster and his men encountered had already been hit by several enemy strikes and as a result, were quick to attack the shoreline. There was no radio frequency to communicate through, so Brewster had to literally put himself in the line of fire to convey they were shooting at American soldiers.

One of his last days in the field, Joe recalls he was to set up ambush positions in one of two locations, the first a particular portion of jungle, and the second an area along a creek bed. He decided to go with the creek bed and set out with 18 men. They encountered no activity that night. It was told to him some time later, that afternoon a Ranger unit of 8 to 10 men went into that jungle area and were virtually wiped out after encountering a full NVA regiment.

He often thinks back to what would have happened if he had chosen the other route.

In October or November of 1970, the 25th was sent home. As a normal tour was 365 days, Brewster still had a month or so to fulfill. He was sent to an in country training school, so he could join the 1st Cav for the remainder of his service. The officer in charge was a Ranger partner of Brewster’s back in training. On the last day, he was offered a teaching position that would prevent him from returning to the field. He declined, thinking it was scarier to talk in front of a class than it was to jump back into that jungle.

Throughout the war, Brewster says he had his Guardian Angel with him and claims he’s the luckiest man in the world. With less than 30 days left in his contract, he never did return to combat. He was told he couldn’t adapt that fast to his new assignment. The second or third week in December, Joe was heading home.

It was around this time he was told the Chief of Staff wished to speak with him. As a lieutenant, at the time he remembers thinking something was very, very wrong. He couldn’t have been more mistaken.

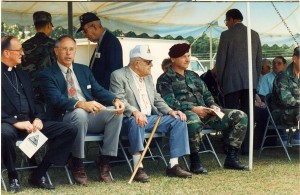

Lieutenant Joe Brewster was chosen to bring the 25th infantry regimental colors to Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. He proudly carried those colors back to America, and it was an honor he knows he will never forget.

One of the saddest things Joe Brewster remembers, is the reception of our Veterans back in 1970. Carrying regimental colors, he was welcomed with open arms and a parade when he hit American soil, while most of his brothers in arms returned to nothing but a hostile environment.

It’s important today more than ever, to read these stories of service, and thank these incredible men.

Joe Brewster decided against a career in the service. He returned to Texas A&M for graduate school and is now a real estate appraiser in the Brazos Valley.

His two sons went on to become fourth generation Aggies.

Lt. Joe Brewster, thank you.

Today and everyday, we salute your service.